The Truth About Limits

Sportsbooks should be able to cut off winners. They shouldn’t be allowed to lie about it.

Last fall, the Wyoming Gaming Commission solicited a report on the practice of “limiting,” where sports wagering operators decrease the amount certain users are allowed to bet. The results are now public, and decidedly pro-sportsbook.

The author, special agent supervisor of gaming compliance Michael Steinberg, wrote, “less than 1% of Wyoming sports bettors are limited” and told reporters that limits were not that severe, typically a “$500 or $1,000 maximum on a market” for patrons who had been restricted.

Steinberg was not sympathetic towards bettors who had been cut off, saying “most of the reason[s] for limiting a patron revolve around the patron ‘cheating’ in some manner.” He listed various ways users could cheat, including placing bets while at live events to get ahead of the sportsbook’s data feed and creating multiple accounts to take advantage of bonuses.

I don’t have access to the data sportsbooks gave Steinberg, and it may be true that Wyoming is unrepresentative of the rest of the country and uniquely full of “cheaters.”1 But based on my experience, conversations with current and former sportsbook traders (the people who actually limit customers) and hundreds of bettors across the country who have been limited, there are some major flaws in his analysis.

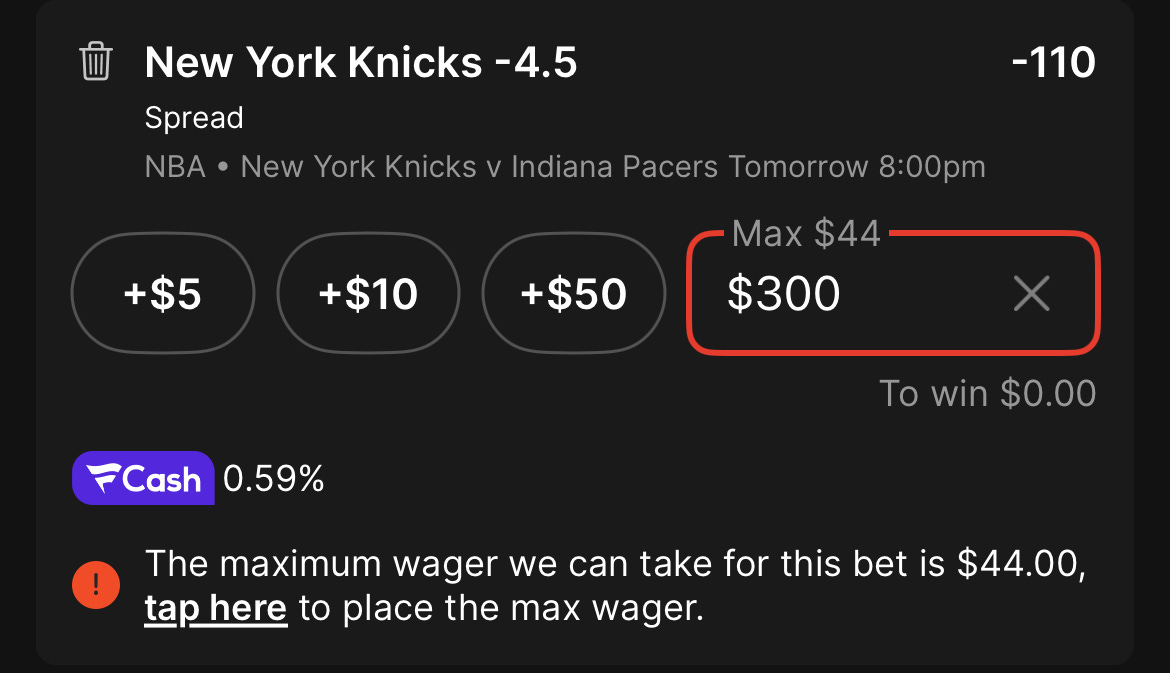

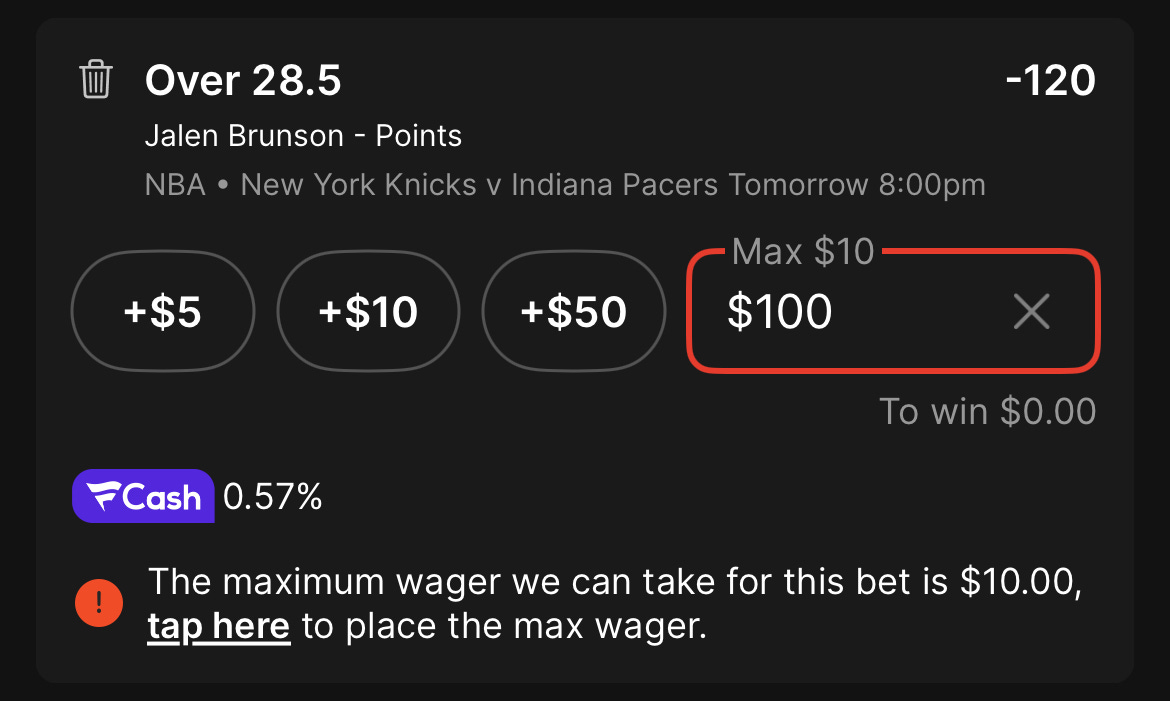

First is that restricted users are not able to bet $500 on most markets. Limits at legal sportsbooks generally come fast and furious; once they decide you are an undesirable customer it’s rare to be able to bet more than a couple hundred bucks on major markets, or $50 on prop and derivative markets.2

Take my own account at Fanatics, one of Wyoming’s five licensed operators. I’ve never “cheated” or engaged in any of the behaviors Steinberg describes, yet once they decided to limit me I couldn’t bet more than $50 on any major market, or more than $15 on any prop market.

Some books are more lenient in their treatment of restricted customers—Caesars deserves credit here, along with Fanduel which offers the highest limits and is the only operator to display max wager amounts before users submit bets—but they are the exception.

The second issue with Steinberg’s report is that most users are not limited for “cheating,” or for engaging in any of the behaviors he outlines. They’re not even limited for winning; after all, if sportsbooks banned everyone who placed a winning bet, they’d have no customers left. Bettors are primarily limited for displaying tendencies which indicate they are likely to win in the future.3

These tendencies take various forms. Decades ago betting on unders and underdogs was enough to get profiled as “sharp.”4 Today, sportsbooks are able to leverage vast amounts of data to accurately identify which customers are likely to be profitable for them in the long run, and which pose a threat to their bottom line—sometimes within just hours of signing up.5

I believe sportsbooks should be allowed to profile and restrict successful customers. They are private businesses with obligations to their shareholders, and winning bettors don’t have a god given right to bleed them dry. Moreover, high tax rates and expanded betting menus make it incredibly difficult to operate modern sportsbooks without decreasing limits or bet options for certain customers.

What’s unfortunate is that Steinberg’s report—and most policymakers' responses—ignore how modern sportsbooks actually operate. This creates problems for customers getting cut off without explanation, many of whom are pushed into the unregulated market. It also hurts low-margin sportsbooks that don’t restrict users and should receive preferential tax and regulatory treatment.

But most importantly, it misleads millions of Americans, primarily young men, who are losing and will continue to lose billions of dollars without understanding that the game they are playing is rigged.

Instead of debating whether bets should be voided if a Belarusian athlete raises a flag, regulators should ask operators a simple question: if a customer uses their own knowledge and data they’ve acquired to place informed bets, and wins, will you limit or ban them?

The answer, of course, is yes. So why are operators allowed to lie in their advertisements, and have celebrities on ESPN tell viewers they can sign up and use their smarts to win big—even though the system is designed to stop them from doing exactly that?

One of the most worrying things about modern sports betting is just how delusional so many users are. 70% of online sports bettors believe they are winning or breaking even, more than twenty times the rate of people who actually win. Bettors who think they can win are more likely to chase their losses, have difficulty quitting, and experience serious harms.

There is a simple way to combat these delusions: mandate sportsbooks tell the truth in their advertisements.6 Sixty years ago, Congress passed the Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act. Since then, study after study has shown that warning labels work. They decrease adoption rates among young people, decrease the number of people who get addicted and are harmed, and increase knowledge about the product among users and non users.

We need a similar act for sports betting, to prevent operators from lying to customers and to make sure Americans are informed about the products they’re consuming. Just as millions of Americans continue to smoke, millions will continue to gamble. The goal isn’t to stop them—but to help them understand the odds.

Whether the behaviors Steinberg outlined or other less than honest ways of gaining an advantage over the sportsbook constitute cheating is a complicated question, and not the focus of this post. To quote Richard Schuetz, CEO of American Bettor’s Voice, “I find the use of the term cheating to be most curious. Am I then to assume that the operators identified these cheaters for the regulators and law enforcement, and we can anticipate arrests and legal actions? If an operator were to fail to report cheating to the regulators and law enforcement, it would seem to jeopardize their licenses. We cannot have operators covering up cheating instances, for it threatens the integrity of the industry.”

Major markets refer to “sides and totals” (who is going to win, by how much, and how many points are scored) for sports like the NFL and MLB. Prop and derivative markets refer to everything else, such as how many rebounds LeBron James will get or whether Aaron Judge will hit a home run. Some sportsbooks limit by sport––meaning if you demonstrate success in basketball they might not restrict you in soccer––but most impose blanket limits.

Sportsbooks like to obfuscate this truth by insisting that thousands of people win all the time, which is a completely different question than whether they permit users who are likely to win in the future. They describe limited customers as “cheaters” or “syndicate” or “algorithmic” bettors to convince normal bettors that those getting limited are somehow evil and not like them, when the majority of the time they are just normal people who figured out how to win.

Most people prefer betting overs because it’s more fun to root for something to happen than something not to happen, which has historically resulted in advantageous odds on “under” bets. The same was true for underdogs, because most people preferred to bet on the better team (the favorite).

The most common way sportsbooks identify winning bettors is by tracking their closing line value (CLV), aka whether or not the odds move in their favor. If I place a bet on the Yankees when they are 5/1 underdogs, but by the time the game starts they are only 2/1 underdogs, I “got CLV” and placed a “good” bet. There are various ways to get CLV, including but not limited to: creating predictive models, identifying discrepancies in pricing between sportsbooks, and gaining access to or synthesizing information before it’s incorporated into the betting line. Bettors who consistently get CLV are almost certain to win in the long run, which is why sportsbooks often limit these users even if they are net losers.

There should also just be fewer, if not zero, gambling ads.

Wyoming's "investigation" basically amounted to asking the books and regurgitating what the books said. This is useful information (that one may as well bet offshore from Wyoming as the effective level of regulation is comparable).

The citation of court-siding is especially telling. If one has to be physically present in Wyoming, where could one court-side, beyond the few University of Wyoming home games?

Well done, Isaac.