There Are Too Many Problem(atic) Gamblers

The Prevention Paradox, and why focusing on addicts misses the point

In a 1981 paper for the British Medical Journal, the epidemiologist Geoffrey Rose observed two major flaws in how doctors treated disease. The first was the “regrettable separation of the therapeutic and the preventive roles,” a focus on those already sick instead of those who might become sick. Preventing disease in many would save more lives than perfecting treatment for the few.

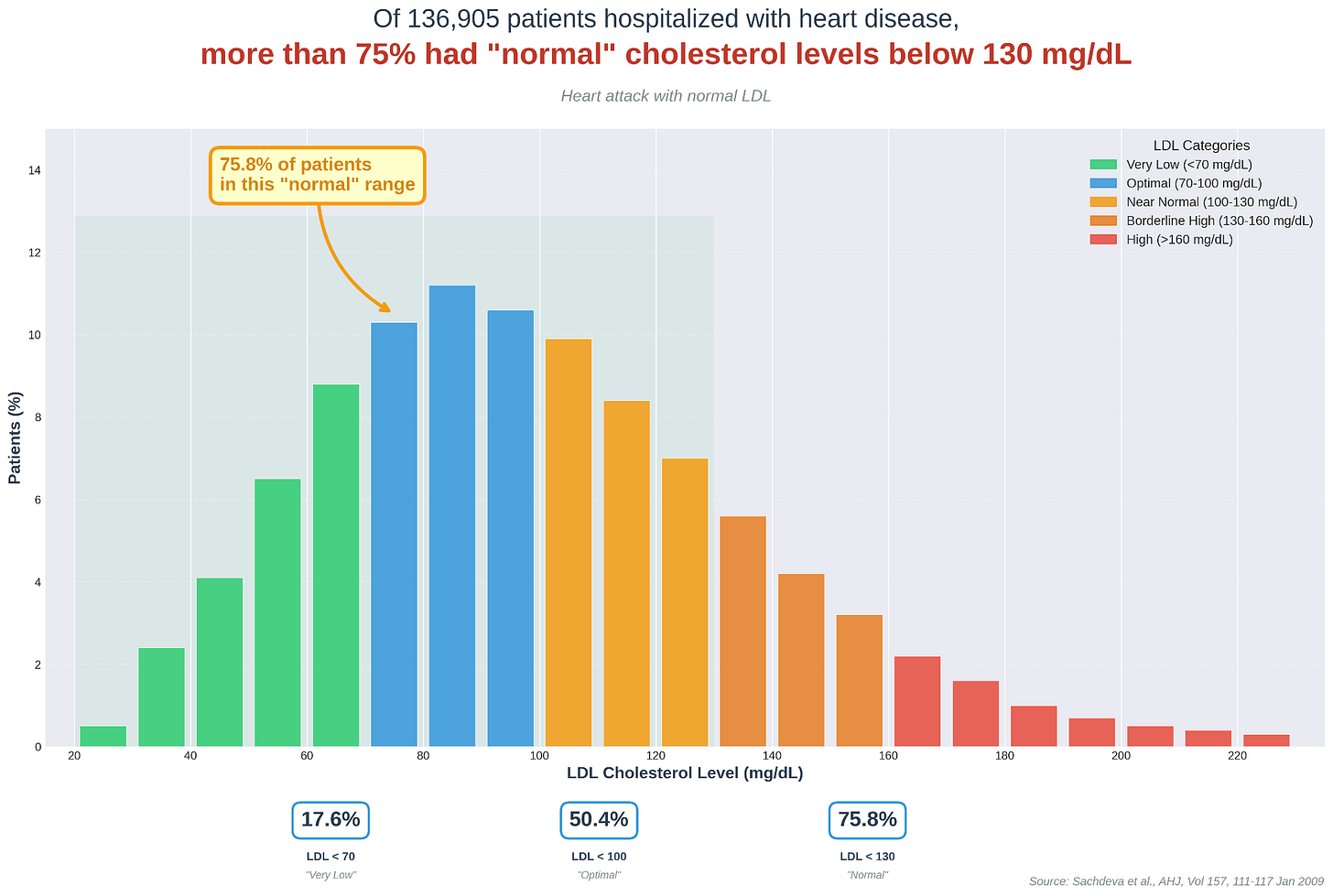

The second flaw lay in how prevention itself was practiced: clinicians were targeting the wrong people. High-risk individuals were getting all the attention, despite accounting for a relatively small percentage of total disease. “A large number of people exposed to a low risk is likely to produce more cases than a small number of people exposed to a high risk,” he wrote. Small risks multiplied across millions outweighed large risks concentrated among thousands.

Rose was measuring heart disease and attacks—clear, binary outcomes. But his insight, what has been termed the “Prevention Paradox,” also applies to harms which exist on a spectrum. Gambling is a perfect example. As researchers at the University of Massachusetts School of Public Health and Health Sciences wrote in a 2021 report commissioned by the Massachusetts Gaming Commission,

A far greater number of individuals experiencing gambling-related harm are low-risk gamblers because there are far more low-risk gamblers than high-risk gamblers in the population. The ‘paradox’ is that more aggregate harm is suffered by the low-risk gambling population even though, individually, people in the high-risk population (e.g., heavy gamblers and those experiencing gambling problems) suffer the greatest amount of harm per individual.

The report found that 70% of all gambling harm arose from lower-risk groups, and was based on data from 2013 and 2014. In the decade since, widespread legalization of sports betting and the rise of mobile gambling—90% of bets in the US today are placed on smartphones—has pushed that percentage even higher, as constantly available, frictionless betting makes it easier than ever to develop a problematic relationship with gambling.1

Some of this can be blamed on the gambling industry’s predatory practices. Online sportsbooks and casinos collect massive amounts of data, which they use to profile users and extract as much money as possible via push notifications, targeted promotions and more. As a judge in the UK recently ruled in a lawsuit against British operator Sky Betting & Gaming (which is owned by Flutter Entertainment, the same company that owns FanDuel, America’s #1 sportsbook and casino), the company engaged in “parasitic” profiling which violated data protection laws through targeting marketing to a gambling addict.

The city of Baltimore filed a similar lawsuit against DraftKings and FanDuel earlier this year, alleging the operators “specifically targeted our most vulnerable residents.”2

Operators are also to blame for the widespread normalization of gambling through marketing campaigns featuring athletes and celebrities—ads that often encourage problematic behavior. Consider FanDuel’s recent campaign featuring the comedian Eric André, where he literally stalks a man throughout his day—while he’s watching sports, when he’s eating, even when he opens the freezer—relentlessly pushing him to “act on his hunch” and place a bet. Another FanDuel ad depicts a man sitting in a pool, staring at his phone tracking bets while his family and friends socialize and enjoy life without him, with the tagline ‘Cherish Every Moment.’

Perhaps the most egregious example came earlier this month, when Stephen A. Smith (who signed a $100 million contract with ESPN, which recently disbanded its own sportsbook), promoted a gamblified version of Solitaire where users compete to win money. In an AI-generated ad for the “World Solitaire Championship” Smith is shown at NBA games, in bed, at yoga class, and even at his own wedding playing the game. “If you want to make it,” the television personality says, “quit distracting yourself, and keep your head in the only game that matters.”

But focusing solely on the gambling industry’s villainy misses the larger picture. These companies aren’t uniquely responsible for corrupting some pure digital ecosystem. The product they’re pushing just happens to be the one with the most immediate and quantifiable consequences.

Every tech company is now in the addiction business. Netflix’s CEO famously said their biggest competitor was sleep. Snapchat and Duolingo punish users who don’t engage daily by destroying “streaks.” TikTok’s feed is a variable-reinforcement machine, adjusting in real time to every pause and replay to determine what hooks you. The swipe feature on modern dating apps was inspired by a famous experiment by the behavioral scientist B.F. Skinner which “turned pigeons into gamblers.” They all use the same manipulation playbook; gambling apps just keep score with dollars, not minutes.3

For a recent STAT news article, I spoke with a college sophomore whose gambling falls into the gap between fine and addicted, where most harm actually exists. “I started checking the odds first thing in the morning,” Danny told me. “I’d wake up, grab my phone, and open PrizePicks before even looking at my texts. Sometimes I’d bet, sometimes I’d just check the lines. Then I’d look again between classes, and during meals. I wasn’t losing a ton or failing out, but it started affecting me a lot… when my bets hit I felt on top of the world, but when they lost I felt like an idiot, and couldn’t concentrate on school or even on hanging out with my friends.”

This is what statistics miss. When people cite “problem gambling” rates of 1-2%, they’re capturing only the most extreme cases.4 It’s like measuring social media’s harm by counting only those in treatment for internet addiction. Examined via another metric—encroachment upon one’s life—the numbers are much higher.

The real tragedy is how unremarkable Danny’s story feels. As Derek Thompson recently wrote in a piece aptly titled The Monks in the Casino, “Americans—and young men, especially—are choosing to spend historic gobs of time by themselves without feeling the internal cue to go be with other people, because it has simply gotten too pleasurable to exist without them.”

There likely won’t be a dramatic ending to Danny’s story. He won’t lose his tuition, drop out or hit rock bottom. He’ll just become a lesser version of himself; more anxious, less present, emotionally tethered to an app that cares most about his lifetime value. Multiply him by millions and you get what Jonathan Haidt calls “the great rewiring”—young people whose brains have been reconstructed to feed on intermittent digital rewards.

Forty-four years ago, Rose concluded his paper on the Prevention Paradox by saying, “the only acceptable answer is the mass strategy, whose aim is to shift the whole population’s distribution of the risk variable.” Mobile gambling achieved that shift—just backward.

Danny’s checking odds, his roommate’s checking TikTok, I’m alternating between writing this piece and checking Twitter. None of us are sick enough to be a statistic, but we’re all sicker than we should be. Small harms, infinite scale. What Rose called a paradox, we call Thursday.

For those lucky enough to not have spent hundreds of hours reading about gambling addiction and disorder, problem(atic) gambler here is a pun on “problem gambler,” the default moniker used to describe people experiencing significant harm from gambling. This of course applies also to all forms of financial speculation, such as trading options on Robinhood or buying event contracts on prediction markets (activities which I would argue often constitute gambling).

For transparency, this piece I wrote last year on this blog is cited in the lawsuit.

Obviously these companies only really care about time spent on app because it translates into profits for them.

My favorite example of this is from a couple years ago in the UK, when gambling advocates went around touting a study that found 0.3% of all Britons (including those who didn’t gamble) had a severe gambling problem, but twisted it to say 99.7% of people who gamble experienced no harm. The UK Gambling Commission then wrote an open letter titled “The Misuse of Gambling Statistics,” which concluded with a plea for “anyone commenting on this area to take a greater degree of care to ensure they are using evidence and statistics correctly, accurately and in the proper context and with any necessary caveats applied.”

Yeah, really nice article. I probably am similar to Danny.

Liked how the article is focused on gambling, but extended to other, similar digital addictions.

Another great article from IRB!