A lot can change in a few seconds. This is especially true in sports, where a single shot can alter the trajectory of a game, season or career. Those moments are what fans live for, and players dream of. They’re also making sportsbooks lots of money.

Until recently, gamblers could only place wagers on games before they started. Poor technology, slow transmission times and complex pricing prevented sportsbooks from offering in-game wagers. Online betting has rendered these problems obsolete. Today’s sportsbooks encourage in-game betting, often including free live streams on their apps. The sportsbook push behind in-game betting is straightforward: if users can bet all throughout the game they’ll bet more, which will increase profits for the house.

In-game betting and its cousin microbetting––where gamblers wager on individual actions, such as whether the next pitch will be a ball or a strike––are here to stay. Users and casinos love them, while sports leagues are happy they increase viewership and fan engagement. But the fast-paced nature of live betting markets also creates more ways for sportsbooks to exploit users. When odds are jumping around shady operators can pad their margins, and it’s almost impossible for customers to notice.

Why In-Game Betting is Different

Most sports bets are simple transactions. Users wager on an event, and if they win get a predetermined payout. All three factors––the bet amount, the event, and the odds––are agreed upon by the gambler and the sportsbook. If you bet $50 on the Warriors to pay $100 if they win, a sportsbook isn’t allowed to charge you $150, change your bet to the Knicks, or only pay you $80 if the Warriors win.

Two of those factors are static. $50 and the Warriors winning are the same at 1pm as they are at 7pm. The odds, however, are dynamic. If a report comes out that Steph Curry is injured, the Warriors odds of winning will decrease, and a bet on them will payout more.

Odds movements usually don’t impact wagers. It takes a few seconds for users’ bets to be processed by sportsbooks, so problems only arise when odds change during that period. If you’re betting on the next day’s Warriors game, it’s unlikely there will be a significant shift in the market in the few seconds after you place your bet.

With in-game betting this is a bigger issue. Games can change in the blink of an eye, meaning there’s a decent chance the odds when a user places a bet aren’t the same as when the sportsbook processes that bet a few seconds later.

Imagine, for example, the Warriors are playing the Lakers. The game is tied with 30 seconds left, and the Warriors have possession. A bettor wagers $100 on the Warriors to win, which stands to payout $200. Right after they place it, Steph Curry makes a three pointer, and the Warriors take the lead. By the time the bet has gone from the bettor’s phone to the sportsbook’s server, the odds have changed: it’s now $100 to payout $120. What should the sportsbook do?

Imperfect Solutions

There are three obvious choices: sportsbooks can void the bet, accept it at the new price, or accept it at the old price. None are perfect. If a sportsbook voids all bets where the odds change, users will go to other sites which will accept their wagers. If they use the market price when the bet reaches the server, they’ll anger customers getting a worse deal; after all, our gambler bet $100 to payout $200, not $100 to payout $120. If a sportsbook accepts all wagers at the price when the bet is placed, they risk being exploited by savvy (or scummy, depending who you ask) bettors who will take advantage of slow-moving odds and lock in profitable bets at outdated or “stale” prices.1

To get around this, most sportsbooks allow users to choose whether they want to manually or automatically accept odds changes. Users who opt for the first need to confirm they want the new price, while those who opt for the second will always get the market price when the bet reaches the sportsbook’s server a few seconds later. Some sportsbooks also have a third option, accept all higher odds, which won’t ask users to confirm if the potential payout increases, but will ask if the potential payout decreases.

For those who don’t bet on sports or don’t understand what I’m talking about, I’ve attached a video example below. In it, the user (me) places a $10 wager on Purdue, which stands to payout $32. In the couple seconds after I place it the odds decrease (move in my favor), meaning my $10 bet now only stands to payout $29.50. Because I’ve opted to review odds changes instead of automatically accept them, Fanduel doesn’t place my bet, and asks me if I want to accept the new price.

On the surface, this choice seems to solve the in-game betting problem. Users like me who opt to review all changes might get annoyed when their bets don’t go through, and users who accept all changes might get annoyed when their bets are placed at worse odds, but they chose their fate. Any missed bets or bad prices are just bad luck, a result of sportsbooks passing on the complications of betting in this fast-paced environment to their customers. If bettors get a raw deal, that’s not the sportsbook’s fault. Right?

How Sportsbooks Can Cheat

It’s easy to understand how in-game betting markets should work when users have filtered their preferences. Bettors who accept all changes get the market price a few seconds after they place their bet, and bettors who want to review changes have their bets voided if there’s a change in either direction.

But imagine a sportsbook is run dishonestly, by people looking to take as much money as possible from users without them noticing. In-game bets present a unique opportunity, due the opacity of the market during the few seconds between when bets are placed and processed. When the odds are jumping around users may not notice if they get a slightly worse deal, or attribute it to bad luck.

To increase their edge, a dishonest sportsbook will maximize the information asymmetry between them and users. The easiest way to do this without customers knowing is to artificially extend processing times. If it takes bets one second to reach servers but the sportsbook tells users it takes three, they can hold onto those bets for an extra two seconds. During that period they can see how the market moves, and decide what they want to do with the gambler’s wager.

This allows sportsbooks to exploit all live bettors, in different ways. For users who automatically accept odds changes, the sportsbook can now give them the worst price available during that period, instead of the true market price one second after they place their wager. If questioned they can cite varying processing times, and say the bet happened to go through when the price was lower.

For users who have opted to manually review changes, the sportsbook can use this two second buffer to see which direction the odds move. If the odds move in the user’s favor, meaning they made a “good” bet, they can void it and say the odds changed. If the odds move against the user, meaning the user placed a “bad” bet, they can accept the wager at a below market price and increase their profits.2

An Example

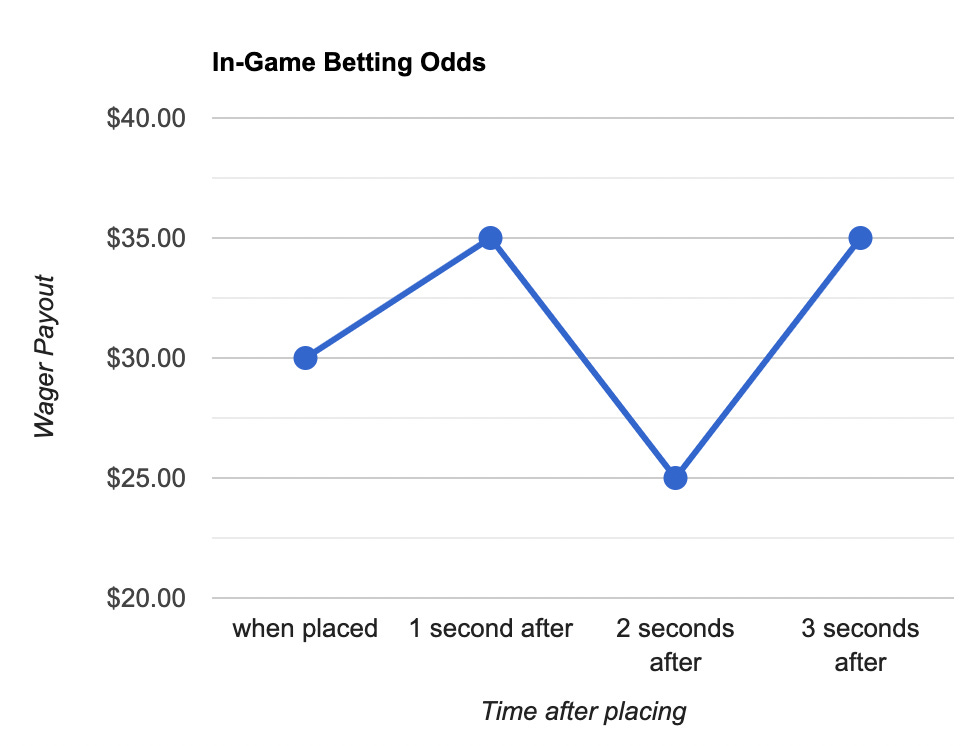

The graph below shows one case where sportsbooks could use artificially extended processing times to take extra money from customers. Imagine Aaron and Max each make a $10 bet on the Warriors which stands to payout $30. Aaron has opted to accept all odds changes, whereas Max wants to manually review odds changes. Right after placement, the odds move around a bunch.

At an honest sportsbook Aaron’s bet will be accepted and payout $35, the market price one second after placement. At a dishonest sportsbook his bet will be accepted but payout only $25, the lowest price in that 3 second period.

At an honest sportsbook Max’s bet will be rejected, because the odds changed. At a dishonest sportsbook his bet will be accepted at the $30 payout he originally chose, but only because the sportsbook knows it should payout $35 (the price after 3 seconds), meaning $30 is a good deal for them.3

Overall, an honest sportsbook will accept $10 in bets which will payout $35 if the Warriors win. A dishonest sportsbook will accept $20 in bets, which will payout $55 if the Warriors win. Assuming a standard 5% house edge on these bets, in the long run the dishonest operator will win more than ten times as much from their customers compared to the honest operator. Of the $20 in wagers they can expect to keep $5, while the honest operator will keep $.50 of the $10 their users wager.4

Does This Actually Happen?

Depends who you ask. According to betting companies, the answer is unequivocally no. Industry insiders I spoke with noted the importance of their reputation, the existing profitability of in-game betting, and the hassle of dealing with regulators as de-facto forces which stopped them from engaging in bet-delays and similar predatory practices.

These all make sense, particularly in a competitive market. If a rumor spreads that one sportsbook is cheating or regulators are constantly investigating them, people will take their business elsewhere. Moreover, the house cut on in-game bets is higher than pre-game bets, usually between 6-7% instead of 4-5%. Since the vast majority of bettors don’t have an edge, this means their expected losses––aka the sportsbooks expected winnings––are about 50% higher for in-game bets. With users losing that much that fast, there’s no need to reach even further into their pockets.

Some outside the industry have a different view. I spoke with over a dozen professional or semi-professional bettors––defined here as people who actually profit in the long run, and thus struggle to place bets because sportsbooks are constantly kicking them out for winning––and all had at least a few live betting horror stories where they believed a sportsbook was at fault. Rarely did the stories end with them getting their money back.

Despite these negative experiences, most of the pro bettors didn’t think companies systemically tampered with the odds on in-game markets, especially not for regular customers (those who don’t pose a threat to the sportsbooks’ bottom line). Only one was convinced sportsbooks had hidden rules to cheat users out of more funds.

They were, however, united in believing that sportsbooks had the ability to change the rules on a user-by-user basis, and regularly did so to protect against winning gamblers. Sportsbooks and traders I spoke with didn’t deny this, but said it was most often used against customers trying to take advantage of them, for example by exploiting slow data feeds, instead of simply winning.

Multiple bettors pointed me towards a 2019 story in Australia, where a whistleblower at Bet365––a British operator which has since expanded to 9 states in the U.S.––said the company “develop[ed] cheating techniques” to take advantage of users. One of those tactics was adding an artificial delay to in-game bets of between 1 and 3 seconds, “big enough to make a difference but small enough for the punter not to notice.” An Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) investigation confirmed the company had flagged certain accounts, all of which belonged to profitable gamblers, and added an additional delay.

Bet365 internally labeled these accounts as “problem customers,” and assigned a special team to monitor their betting history. Last month, the company joined six other operators to form the Responsible Online Gaming Association (ROGA), which plans to tackle problem gambling in the U.S.

Moving Forward

Of all the problems with sports betting in the U.S. right now, delayed bet processing for in-game wagers isn’t high up on anyone’s list of priorities, and it shouldn’t be. But increased attention towards other problems, such as misleading marketing and lack of funds for gambling-related research, shouldn’t obscure the fact that sportsbooks are offering a financial product and it needs to be regulated as such.

Sports betting isn’t currently regulated at the federal level. When users have complaints they file them with state gaming commissions, which each have their own set of rules. In general, investigations hinge on whether there was a breach of contract; whether the sportsbook acted in a way prohibited by their own terms and conditions.

Some state gaming commissions have additional rules and regulations, but they mostly defer to casinos. A New York Times survey of states which legalized sports betting found that “the enforcement of rules has been haphazard, that punishments have tended to be light or nonexistent and that regulators are counting on the industry to police itself.” None of the sportsbook traders I spoke to knew of any regulation or internal rule which explicitly outlawed bet-delays for in-game wagers.

In Australia, the chair of the Northern Territory Racing Commission––the regulator for sports betting in the region––was asked about Bet365’s reported predatory practices. He told ABC News, “If there was some deliberate action taken to delay … that's something we would have jurisdiction to look at, in particular, whether that, I guess, complies with their licence conditions, within the terms and conditions of their contract."

Hopefully U.S. regulators take a more proactive approach.

The few second delay serves as extra insurance against this group, who sometimes attend games with the intent of transmitting data fractions of a second faster than sportsbooks to achieve an edge.

Sportsbooks make money by ensuring every market has a house edge, aka “Vig,” which is normally around 5% although sometimes as high as 30%-50%. In general, they don’t care which side users bet on, because they take the Vig regardless. But if they can accept a bet at odds below the market price, they’ll make much more than 5%.

Max’s best case is getting a $30 payout when he deserves a $30 payout, but he might also get that $30 payout when he deserves a higher payout. In gambling this is called a “freeroll.” Max is exposed to downside risk, but have has upside potential. He can lose, but can’t win. (By “lose” I mean get their wager accepted at a worse-than-market price, and by “win” I mean get their wager accepted at a better-than-market price.)

These are long-run expected profits. If the “true” payout for a $10 bet is $35 and the market has a 5% house edge (Vig), the bet should win about 27.2% of the time. The honest operator is accepting a $10 wager which will payout $35 if it wins, making their expected profit 10 - (35*.272) = .48. The dishonest operator is accepting $20 in wagers which will payout $55 total if they win, making their expected profit 20 - (55*.272) = 5.04.

Hi Isaac, I'm a journalist with Vixio GamblingCompliance in London, I wanted to get in touch to speak to you for a responsible gambling story I'm working on. davida@vixio.com